The Double Death of Camille Frugier

“I am alive — and I remember” — Agnes Varda

The French government promised war orphan Monique Frugier — and hundreds of thousands like her — a monthly stipend for life in 1946. No one has ever received a cent. To make matters worse, Monique is owed reparations for the long-concealed fact that the death of her father resulted from friendly fire — a tragedy the deceased heroically tried to prevent.

By David Federman

This story is an attempt to collect a debt.

French war orphan Monique Frugier is owed at least 27,400 Euros by her government. This is the official amount France has already awarded since 1995 to each Jewish and non-Jewish orphan who lost a parent to German barbarity. Monique figures she is worth just as much as these victims.

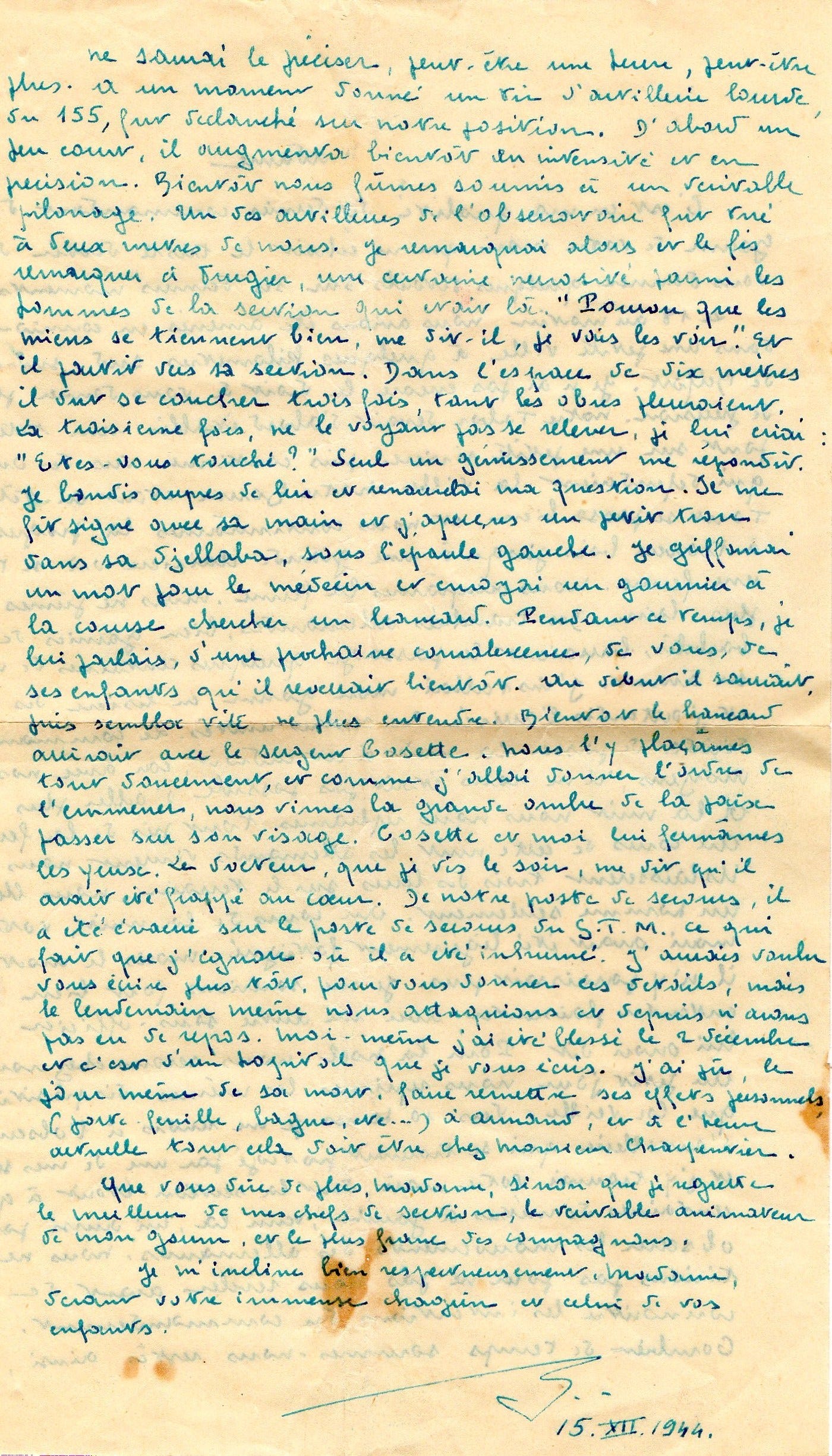

But that is not how the French government figures things. Although her mother was promised a life-time pension for her three children as token of gratitude for her husband’s sacrifice, neither Monique or her sister have yet to see a cent. The two are the surviving children of war hero Camille Frugier, killed during the Battle of Belfort on November 19, 1944. (His son, Alain, died in 1980).

A cynic might be tempted to see her journey to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the Belfort victory on November 22, 2014 — mind you, at the personal invitation of the city council — as a belated request for payment. Monique does not deny that war-debt collection is often on her mind. But she pushed “dunning” to the back of her mind during her two weeks in France.

Ironically, her presence in Belfort stemmed from an on-line article a year or so earlier about the scandalous arrears into which France had fallen in keeping its pension-pledges to its war orphans. Actually, “arrears” is a misnomer. You see, France never authorized a single franc (now Euro) to be paid to these survivors.

That’s right: France has played a Zero Sum Game with its war waifs.

Only it’s not a game, especially in Monique’s case.

If any class of war orphan deserves reparations, you would think it was those who owe their lamentable status to French military error and negligence. Camille Frugier was one such luckless combatant. His death was entirely needless — caused by friendly fire. As a commanding officer, he called off the bombardment that killed him — the day before it happened. The French high command had 24 hours to get things right — yet got them wrong.

And here’s where this story begins. Up until the day before Monique attended the invitation-only memorial lunch and ceremony for the Free French soldiers killed at Belfort, she thought the cause of her father’s death was enemy fire. That’s what the official report, issued in December 1944, had led her mother and later her three children to believe. “Heavy artillery,” presumably German, was the phrase the French officer assigned to furnish details of the death wrote.

In preparation for the event, Monique asked a local reporter, Andre Enderlin, who had written several articles about her father in the months before the anniversary, to take her to the farm where he had been killed. Just minutes and meters away from the farm, the journalist’s cell phone rang. A woman, claiming to be the niece of an eyewitness to the incident, asked if Monique was in the car. When Andre answered yes, she pleaded with him to bring Monique to a different farm, a short distance away, to meet the last living eyewitness to Camille Frugier’s death. “My aunt wants Monique to know the truth,” the caller said. “She has been waiting 70 years for this moment.”

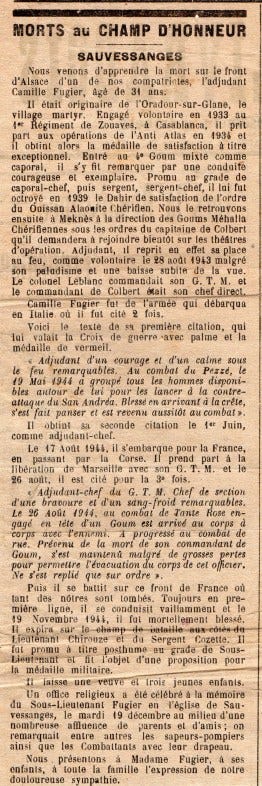

MIS-REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST: The letter to Céline Frugier, dated December 15, 1944, describes her husband’s final moments during the decisive battle of Belfort Gap in eastern France weeks earlier. Writing from a hospital where he is convalescing from war wounds, commanding officer Chirouse (no first name is given or has ever been found) tells with tender eloquence how his most trusted platoon leader, Camille Frugier, died quietly after being hit by shrapnel in “a heavy rain of 155mm [howitzer] fire.” As he breathed his last, Chirouse writes, “the great shadow of peace passed over his face (la grande ombre de paix passa sur son visage).”

Ever since this letter was found in her mother’s belongings after her death in 1979, Monique Frugier has used it as solace for having never seen her father; for having become a war orphan at the age of 8 months. Whenever she is asked how he died, she cites its moving account of a war hero’s death from German artillery fire while defending a French position on November 19, 1944. This was three days before the Free French army victory finally drove the Nazis from Belfort and gave the Allies a key entry point for the invasion of Germany in February 1945.

Seven decades later, Monique went to Belfort for the city’s 70th anniversary celebration of its liberation. A personal invitation from the town council to a commemorative luncheon, November 23, 2014, made it impossible not to attend. But once she decided to travel to France, she also decided to make this day of public observance the culmination of a private pilgrimage.

Monique knew this journey would be more solemn than sentimental. after a week in Paris, her itinerary became purely biographical, meant to chart a time-line of her father’s life and times and death in France.

The pilgrimage part of her sojourn began on the 70th anniversary of her father’s death, four days before the ceremony, with a visit to the Nazi-massacred village of Oradour-sur-Glane, where her father was born on January 26, 1914. Site of the largest genocide in France during WWII, it was decreed a war memorial in 1946 — one to be left in a state of perpetual ruin. This was her first visit since her mother took her there as a child. Although Monique distinctly remembered her mother pointing out the burned-out house where her father’s family had lived (before moving away in the 1930s), she tried in vain to distinguish this hulk from all the others that once served as homes.

Oradour is not meant for homecomings or reunions. The only aids to identification of its former inhabitants and their addresses are plaques nailed to walls naming the businesses and sometimes building owners on the town’s last day of existence.

Except for the burned-out frames of cars, skeletal remains of sewing machines, mangled baby carriages and various twisted mementos that dot the ruins, all the buildings share an anonymity of annihilation.

Because she was in Oradour to honor her father’s death, and because only a fraction of the 642 people murdered there have been identified, Monique views the ghost town with devotional grimness. To her, it is a mass grave rather than a massive monument. Throughout France, one finds tombs of unknown soldiers everywhere. But here, 15 miles southeast of Limoges, is what she bitterly remarks as the country’s sole “tomb of the unknown citizen” (or, more accurately, citizenry). This viewpoint is justified by the arc of Monique’s journey that began in Oradour and ended at the military cemetery in Rougemont (outside of Belfort) where her father is buried.

No wonder she hoped the official remembrance in Belfort would lift her spirits. Before leaving for France, she talked with friends about how she looked forward to joining the hundreds of other honorees and guests in bowing heads and raising glasses to the memory of those, like her father, killed by enemy fire.

That was not to be.

Monique learned — with unexpected, shattering suddenness— that her father died by “friendly fire”.

TWIN TOMBS OF BIRTH AND DEATH: The term “friendly fire” dates from WWI, where a mammoth minority of soldiers crawling through barbed wire or huddled in trenches were killed by their countrymen, not their enemy. On the afternoon of Friday, November 22nd, Monique was told by an eyewitness that her father was killed by “his own people.” Lydia Burkhalter Millier described his last minutes in painstaking detail to her and journalist Andre Enderlin. It was the first time she had spoken publicly about the tragedy since meeting with Camille Frugier’s parents after the war. It was they who told Lydia more about her father’s family than she had ever been told by her mother. Lydia said she had always longed to meet Camille’s children and share with them all she knew about the man who had saved her life and those of her six younger brothers and sisters — and paid for doing so with his own. For Lydia, looking at events through a prism of gratitude, Camille’s death had always been part of greater exchange of lives that spared her large family from destruction. For this reason, she hoped learning the truth about it woild make its pain more bearable for Monique.

Indeed, Lydia’s candor seemed a mercy because it provided a link between Camille’s life as a war hero and Monique’s as a peace activist. Her father’s birth in Oradour and death in Belfort suddenly took on a solemn symmetry that connected and deepened both facts with profoundly personal dignity. Death by friendly fire made Frugier as much a martyr as any of his townspeople. In fact, one could think of him as Oradour’s last victim. This proportionality gave insight and inevitability to Monique’s career as a war resister.

Even Andre gained uplift from Lydia’s disclosures. When the French army surrendered in June 1940, Andre’s father was taken prisoner and forced to work as an iron miner in Germany for the duration of the war. Given the fact that thousands of his fellow Alsatians were later forced to fight for the Nazis and participate in German genocides, those five years of captivity and hard labor seem a far more preferable, even merciful, plight.

Of course, Lydia had no way of knowing the depth and degree of the focus she was contributing to the lives of her visitors. Yet she sensed a need to hear her story as great as her need to tell it.

Lydia, then 88, had kept her story as a guarded secret to be shared only with members of the family whose father saved her family. In November 2014, that left only two Frugiers in whom to confide: Monique and her older sister, Chantal. The surviving siblings’ mother, Celine, and older brother, Alain, both died decades earlier.

Ordinarily, one might have expected Monique and Chantal to make this pilgrimage together. But the sisters have an incurably contentious relationship which prevented Monique from even thinking of informing her sister of her presence in France. When I asked her why she didn’t contact Chantal, Monique answered that the two never discussed their father’s death and that her sister would want no part of this journey.

Knowing what I knew about Chantal, a reunion of the sisters on this occasion would have been ill-advised, if not impossible. A former pop singer with a few minor hits in the 1960s, Chantal went to India to study Hinduism in the 1980s. Like many converts to Eastern spirituality of the time, she had felt it necessary to “renounce” her wild and worldly past, disposing of any and all belongings that might remind her of her former life.

Unfortunately, as part of this eradification of personal history, she buried a cache of letters her father had sent to his wife before and during the war in a wooded spot whose location she long ago forgot. Chantal found this trove of correspondence stored in a closet shortly after their mother died of breast cancer the day before her 60th birthday on September 6th, 1979. Whether or not her sister ever read them she has never revealed. But it is clear that she never showed them to anyone or thought it important to do so, including her siblings. Monique had emigrated to America in 1968 and their oldest brother, Alain, an artist and activist, had been diagnosed with the carcinoma that killed him less than a year after their mother, on March 31st, 1980, aged 40.

In light of all the unanswered questions about her father’s life as a father, husband and, above all, soldier, Monique remains justifiably furious with Chantal for never offering her the opportunity to read her mother’s mail. As Monique put it, “You keep letters as a record for others. My sister just assumed that what was right for her was right for everybody else.” [This writer, who pursued a parallel path of “renunciation” in the 1970s, knows well the pitfalls of such aggressive austerity. As a consequence, I have little or no record of my family or my personal history.]

In any case, with no other relics from her father’s past than a box of medals, legal documents and an official letter of condolence, Monique tried to reconstruct her father’s life and death as best she could. As far as she knew at that moment, days before her visit to Belfort, there were no known survivors of the bombardment which took her father’s life. Until then, she will meet the last living witness of her father’s death, she did not know that long-awaited reconstruction of his death would be more a deconstruction.

THE MONEY TRAIL TO AND FROM NOWHERE: In hindsight, the meeting of Monique Frugier and Lydia Burkhalter Millier had an air of inevitability to it. It was the result of an article on Camille Frugier’s life and death that Enderlin had written for L’Est Republicain, eastern France’s largest regional newspaper, on October 28th, 2014. Months earlier, Enderlin had been told to get in touch with Monique by a blogger who had published an anonymous article by a man who signed it, J. M. The article, apparently one of many, resumed pestering the French government to make good on its promises of pensions for war orphans — obviously, to no avail. Monique, who had been forwarded it, had written from America to protest this injustice — and predict it would continue until every surviving war orphan was dead. In the meantime, Andre and Monique struck up a lively email correspondence and gradually Andre decided he had to write about this fiery peace activist.

When Lydia read Andre’s stirring article, “Born in Oradour; Died in Belfort,” on its day of publication, and learned from it that Frugier’s daughter intended to attend the Belfort celebration, she made a note to contact the author. But she delayed until the eve of the event, asking a niece call the newspaper to arrange a meeting with Monique. The newspaper gave her Enderlin’s home number and Enderlin’s wife, in turn, gave her his mobile number. Less than a mile and a minute away from the farm where Frugier died, Enderlin’s cell phone rang and he pulled over to the side of the road to answer it. The caller explained that Lydia was waiting for Monique at her home. As Enderlin wrote down directions, he realized Lydia lived an even shorter distance away. “Oh my God,” he exclaimed to Monique, his son Eric and this writer in the car with him, “she has lived all these years just down the road from the farm where Monique’s father was killed.”

Once at Lydia’s farm house, Enderlin went ahead to introduce himself. Lydia opened the door and waved Monique to come inside. After apologizing for the imaginary unkemptness of her spotless kitchen, Lydia asked her guests to be seated at a large baronial breakfast table and served refreshments. Once everyone was settled and pleasantries exchanged, Lydia began her chronicle of Camille Frugier’s death.

It contradicted Chirouse’s at every key point. Then 18, the young woman had watched the tragedy unfold from the upstairs window of the farmhouse where she and her family had been hiding for months. Her father, a known member of the French Resistance, had been the object of a Nazi manhunt, but had escaped weeks earlier, along with his two oldest sons, to their native Switzerland. Hence there was no longer any reason for German interest in the farmhouse. Yet the French high command still believed the dwelling was a Nazi base of operations and earmarked it for destruction on November 19th. Despite radio notification by Frugier 24 hours in advance, headquarters ignored information that his unit had occupied the Burkhalter farm and been given permission by the family to quarter for the night in its barn. Technically, Frugier had disobeyed orders since he had been told to keep his men stationed in the woods next to the house. But suspecting an attack unnecessary, he advanced to the farm and found it free of Nazis. Frugier then sent an all-clear to headquarters and requested the bombardment scheduled for the next day be called off.

Nevertheless, heavy shelling began as planned at 10 AM the next morning. Although Chirouse’s letter states there was howitzer fire, Lydia, understandably unversed in the differences between medium and light artillery, thought she was seeing a mortar barrage. Perhaps it was a mixture of both. In any case, all hell broke loose. “Shells fired from behind began exploding everywhere,” Lydia told her guests. Addressing Monique, she recounted the brief ensuing massacre with chilling, chiseled accuracy: “Your father was hit from behind in the left shoulder. His left arm went limp and seemed to be hanging. He was bleeding profusely. [Chirouse had described the same injury as “a small hole” that served as entrance to a piece of shrapnel that caused a heart attack.] Your father fell down, managed to get up, staggered a few steps, fell down a second time, got up a second time, then collapsed on the ground. As some of his men were carrying him into the house, he cried ‘Maman! Maman!’, and died.”

LYDIA’S BOMBSHELL: Let us pause here for some profound cognitive dissonance on the part of Lydia’s listeners, all of whom had, until then, no reason to doubt the veracity of Chirouse’s letter. Enderlin wrote his article based on it. Monique’s owed her whole understanding of her father’s life to it. Without intending to do so, Lydia was saying this crucial account of Camille Frugier’s death was, for the main part, a fiction. A man who died for France was, in reality, killed by it. Did that fact diminish his valor to vainglory?

Yes and no. But far more no than yes.

Okay, Chirouse can be excused for camouflaging a tragic accident of war. After all, Frugier had already received three medals for bravery and had earned eulogizing as a hero. Moreover, the letter was written during war time and risked censorship if candid.

Understandably, Enderlin tried to explain the cover-up as a necessity of the moment. As Charles de Gaulle said when he banned televising Max Ophuls’ tell-all documentary about Vichy France, “The Sorrow and the Pity,” in 1969, “The people need hope, not truth.”

But 70 years later, didn’t the need for truth finally outweigh the need for hope? Monique openly wondered if the falsifications meant to fortify her mother in wartime shouldn’t have been corrected in peacetime. By allowing Camille Frugier’s death to be grouped together with the majority of his comrades killed by enemy fire, wasn’t her father death by friendly fire deprived of a special cautionary importance? “Despite his bravery, my father died a war victim, not a war hero,” Monique told me later, “For the good of all, I think his final dignity should come as much from the senselessness of his sacrifice as its nobility.” She paused, inhaled, as if she was smoking, and then exhaled: “For chrissakes, his death was avoidable. I would have had a father if some idiot hadn’t ignored his message.”

MARTYRDOM, ANYBODY? It was, and is, not easy to adjust to thinking of Camille Frugier as a martyr. Monique had spent her life thinking of him as a warrior. Nevertheless, hearing the truth from Lydia somehow spared her new wounds. Maybe it was the compassionate urgency with which Lydia told the story of his last day on earth. As she listened, Monique told me afterward, it was like an exorcism. “It felt like she had been keeping a lone vigil over my father’s memory, waiting to invite me to join it.”

Because the history being remembered was so intimate, immediate and, above all, immutable, it hardly seemed surprising when Lydia told Monique and Andre that she hasn’t seen fit to visit the scene of his death, no more than a couple of city blocks away, of la erreur grave since 1962.

There had been no need — at least not a solitary one.

Until now.

Until the need could be shared.

Lydia volunteered to escort Frugier and Enderlin to the place where Camille Frugier was killed and to guide them through the chronology of what she repeatedly called his “sacrifice.” As we approached the farmhouse, Lydia pointed to a large window on the floor above the wide kitchen entrance. “I saw it all from there,” she exclaimed. Then she described the exact trajectory of the tragedy, pointing her finger to each of the successive places where Camille Frugier was first hit, fell, got up, tried to run forward, fell again, rose a second time, and, finally, collapsed. As Lydia meticulously narrated, there was a seance-like hush as if she were summoning, or consulting with, the spirit of the man she feels saved her life. Moved by Lydia’s careful, custodial account of her father’s death, Monique later concluded, “The memory of others is our only afterlife. So if you want to go to heaven, you better leave good memories behind with those who will remember you.” This was the most religious remark I had ever heard from her.

Although Lydia is a devout Catholic, her companions are agnostics and atheists who have struggled all their adult lives to live with war, knowing no sense can be made of it — or a God who would allow it. Monique who is an unrelenting crusader for the separation of church and state (“the First Amendment defends freedom from, not of, religion,” is her mantra), is fond of ridiculing the all-loving Father-God she was taught to worship during her Catholic childhood in Morocco. “What loving father would send his sons to die in battle?” she will ask defenders of any faith her friends profess. Knowing now that her father died by friendly fire, she feels her atheism affirmed and fortified.

Like many who ridicule religion, Monique still subscribes to spirituality. She believes in a moral universe — one that steers the mindful and deserving to various graces ranging from good luck to great wisdom, depending on the needs and receptivity of the beneficiary. As a pantheist, she felt this afternoon was preordained; that private quests of all present were being completed in a public profusion of providence. It was impossible not to agree.

Still, the truth took some adjusting. I peppered Lydia and Andre with questions about the inconsistencies between Chirouse’s and Lydia’s accounts of what Andre had decided was an “incident.” Finally, Lydia stopped my questioning by saying, “What does it matter how he died or who killed him? He was a hero.” I felt light years away from such understanding and forgiveness. But I freely allowed myself to bask in hers.

Later, as we drove back toward Belfort, Monique confided that she was now ready to believe her mother tried once to convey suspicions about the official version of her husband’s death. “I have always resisted accepting her doubts,” she confided. “Lydia has convinced me my mother was right.” She paused, then whispered to me, “How I wish I could have confirmation of her story, so it wouldn’t be one person’s word against another’s.”

The next day, a friendly firmament granted her wish.

THE CURSED LEGACY OF ORADOUR: For two years before he wrote his October article, Enderlin had been in close touch, mostly by email, with Monique. He had been given her name by a blogger who had seen one of her many hundreds of anti-war letters to editors, politicians and pundits protesting surging American militarism since 911. In a few of these letters to French publications, she cursed France for betraying war orphans like her. In letter after letter, Monique described the ceaseless sorrow of never having seen her father and how the desire to prevent her pain from being inflicted on others had motivated her to become an activist. Moved by these letters, Enderlin was determined to publish a story about Camille Frugier’s full army career and the circumstances of his death. It took two years to uncover the official story, which Enderlin had no reason to doubt.

Frugier was born, January 26, 1914, in the doomed village of Oradour-sur-Glane. There on June 10, 1944, four days after the Allied landing at Normandy, the 2nd SS Panzer Division “Das Reich” slaughtered 642 townspeople, 192 of whom were children as young as eight months old.

Although Oradour was home to Communists fleeing Franco’s Spain, as well as Jews fleeing Vichy deportation, its choice as a target was arbitrary. Such fugitives were scattered throughout small-town Eastern France. The massacre there was taken as both as a random reprisal against the Allies and a warning to the French people not to aid the growing Resistance.

Oradour was not an isolated event. It was the last and greatest of a series of increasingly barbaric and desperate war crimes against the captive citizenries of French cities and towns begun in May when an Allied invasion seemed imminent. By then, the German tactic of collective punishment was standard, dating back to 1941, when Hitler invaded Russia.

DIVIDED LOYALTIES: It would be ill-advised to see Oradour only in a black-and-white context of occupier savagery or revenge. Of the 200 soldiers in the Wafen SS division that destroyed Oradour, many, possibly most, were Frenchmen from the eastern, German-speaking and Vichy-sympathetic region of Alsace. Indeed, the vast degree of collaboration between the Germans and the French deepens the horror and incomprehensibility of the tragedy. Defenders of the Alsatians excuse them as unwilling executioners who had been forcibly conscripted into the German army and were obliged to follow orders.

Given pervasive pro-German nationalism present in the Alsace region for centuries, this defense karate-chops credibility. It was well known that Alsace had contributed many leaders to the enthusiastically cooperative Vichy government which administered Occupied France. It was equally well known that Alsace was a main source of recruitment for the dreaded Milicie, the French paramilitary force created in early 1943 by the Vichy government to track down Resistance members. Vichy leaders no longer trusted the French police to do this work. Only Nazi sympathizers would do.

Advocates of leniency or forgiveness for Vichy participants in the genocide argue that the very pro-German milieu of eastern France encouraged a kind of deranged conformity with Nazi edicts. Never forget, they’ll tell you, that fascism was strongly embraced throughout Europe. On top of this, centuries-hardened cultural identification with German culture contributed to Alsatian participation in war crimes. Nevertheless, does following official orders to kill the innocent shield the killers from prosecution for their obedience?

Advocates for punishment flatly reject any rationale that would exonerate their countrymen. By following orders to kill and later desecrate bodies to make identification impossible, the Alsatians became, at the very least, willing accessories to Oradour war crimes. Hence they should have paid for their crimes.

The debate over French complicity in the Oradour calamity continues to this day — only with added meaning. Given rising French xenophobia against immigrant Arabs and Africans, many from former French colonies, the debate ignores the central issue of modern mass murder: ethnic cleansing. Viewed in light of continuing history, Oradour is both reminder and portent. It looks as much forward to Srebrenica, scene of a Bosnian massacre of 7,000 Muslim men in July 1995, as it does backward to Lidice, scene of a Nazi massacre of 173 Czech men to retaliate for the assassination of a single SS officer. Ironists take note of the date of the Lidice slaughter: June 10, 1942 — exactly two years before the larger-scale extermination at Oradour.

In many ways, Oradour has more contemporary relevance than Belfort in any historical reckoning with WWII. On February 15, 1953, eight-and-a-half years after the genocide, a French war crimes tribunal meted out mild prison sentences of five to eight years for 13 of the 14 Alsatians who took part in the massacre. The remaining defendant, a sergeant who admitted leading a firing squad, and told the court he had no regrets about it, was sentenced to death.

The trial divided France so deeply the verdicts were announced in the middle of the night to prevent rioting on the part of those who wanted bygones to be long gone. Incredibly, public opinion was so heavily weighted against sentencing any Alsatians for the crimes of the Germans that a fractious, frightened French National Assembly pardoned the 14 defendants five days later. They did so on grounds of “national unity.” As it had threatened to do if the verdicts were overturned, the town of Oradour returned the Legion of Honor — the highest France gives for service to the country — presented to it after the war. In a public statement, the town council said the amnesty “martyred the victims a second time.”

A THEME PARK FOR GENOCIDE: If one was enough of a masochist (or, for that matter, sadist), they could organize a very busy tour of Western and Eastern Europe’s martyred villages since 1941. For Monique and I, a visit to Oradour on November 19, 2014 — the 70th anniversary of Camille Frugier’s death — satisfied all curiosity about such places. Since 1946, Oradour has been a carefully preserved ghost town meant to serve as a permanent reminder of the thoroughness and determination with which armies conduct mass destruction. For Monique, however, it has the grim double distinction of being her father’s birthplace (in 1914), as well as a sprawling open-air mausoleum. Just take one slow, sweeping look at the jagged skyline of ruins, then lower your eyes to the disheveled panorama of charred walls with their gaping doorways and windows. You will be forever instructed in the ways and means of genocide.

Like most museums (this one devoted to human horror), we entered through a gift shop. There we found practically every known book and video on the tragedy for sale (we bought a superb documentary, “Une Vie Avec Oradour,” and Douglas Hawes’ important tell-all book, “Oradour: The Final Verdict,” from both of which I have drawn much information about the massacre). This anteroom has an auditorium and various exhibition alcoves. In one of the largest of these niches, the names of the dead who have been identified (most of the victims remain unknown) are read in a continuous-loop presentation. As each name is pronounced, a photo of them or their belongings appears on a screen large enough for use in Times Square. Where neither portrait or possession has been found to synch to, there is a blank screen.

In some ways, the book store and exhibition hall serve as a local anesthetic for the pain of the unrepentant reality one is about to encounter. Never forget that Oradour is meant as much for cure and prevention as remembrance and sorrow. As Monique and I walked up its forever-deserted main street, the village graphically reminded us of the recent horrors of Syria, Iraq, Palestine, Lebanon and Yemen. “Oradour makes me realize that any town can become Oradour at a moment’s notice,” she whispered to me, pausing in her videotaping of the devastation. “I still remember seeing news footage of the first moments of America’s ‘shock and awe’ blitz on Baghdad.”

Monique is right. Oradour is a city turned into a necropolis. But don’t stop taking its measure merely as a memorial to WWII. It also serves as a universal symbol of ceaseless, far greater war destruction everywhere. As a Jew who has avoided visits to sites of the Holocaust, or places where it is conjured, Oradour teaches lessons about contemporary genocide no holocaust museum can. It teaches that genocide practices diabolical equality and can turn any man, woman, or child into an enemy of the of the State — whether it is a Christian, Islamic, Jewish or even Surveillance state. In a world of ethnic cleansing, anyone and everyone is eligible to become a ‘Jew’ or whoever is the designated demon of the day. The continuing resonance of Oradour travels far — from Darfur to Gaza. Its message is this: By simple fiat, a town can be converted into a death camp; its entire population declared subhuman, and summarily executed or subject to steady attrition by murder.

Now I see why Monique chose to begin her pilgrimage in France at Oradour. It is a reminder of the inextricability of her father’s life from war, and death at its hands. There is a fearful symmetry to a life that begins in the martyred village of Oradour and ends in martyrdom on the outskirts of Belfort. After Monique finished photographing the rusted remains of sewing machines, buckets, baby carriages and other relics of domestic tranquility, I ask her if she can ever forgive the perpetrators. She sidesteps the question by framing forgiveness as a collective commitment to a war-free way of life, “The only way the dead of this village want us to honor them is for everyone who visits here to resume the peaceful daily life that was taken from them.”

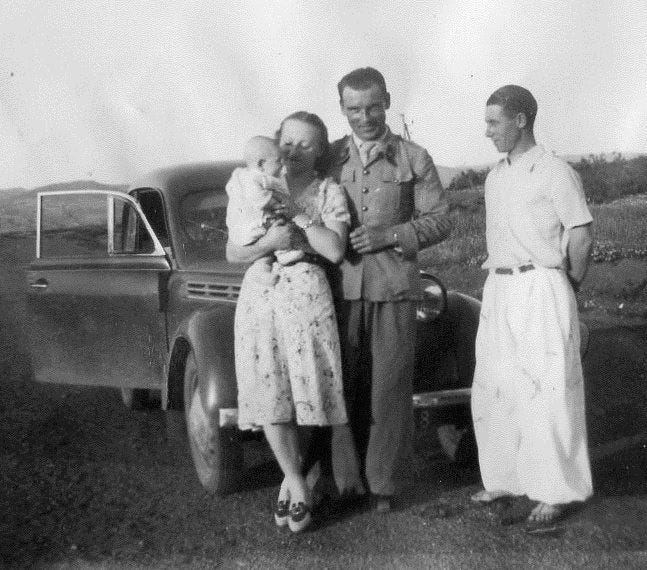

MUSLIM FREEDOM FIGHTERS AND THE LIBERATION OF FRANCE: The Frugier family moved away from Oradour in the 1930s. Camille, who joined the French army in 1933, was stationed in Morocco. Monique’s mother never talked about the nature of his duties in the North African colony or if he knew the fate of his hometown. All that she ever mentioned is that he was attached to the famed Moroccan auxiliary army units known as Goumiers (from the Arabic word, goum, meaning “of the people”) in 1942.

Despite supplying between 50,000 and 60,000 mercenaries between 1936 and 1938 to fight for Franco in Spain during that country’s civil war, Morocco turned decidedly anti-Axis in 1939, sending 20,000 troops to fight against Hitler in France. Moreover, when France fell in June 1940, and tried to impose the new Vichy Regime’s anti-Semitic laws, Sultan Mohammed V, the country’s ruler, refused an order to round up its Jews for deportation. “Moroccan Jews are my subjects, and my duty is to protect them against any aggression,” the Sultan wrote to Paris. By November, he had firmly sided with Roosevelt, whom he had met twice, and committed troops to Free France.

That alliance between Morocco and De Gaulle supplied France with some of its best fighters in the war. The creme de la creme of these warriors served in the Goumiers.

First formed in 1908 to aid in French colonial activities (and disbanded in 1956 when Morocco gained its independence), this volunteer army became a renowned fighting force during World War II. Its various divisions, known as tabors, distinguished themselves as ferocious hand-to-hand fighters — first in North Africa in 1942, then the mountains of Sicily in 1943, reaching France in 1944 where they helped win major victories in Marseille in May and Belfort in November. As a result, there are some French people like Monique who feel France owes the Arabs of Morocco a debt it has yet to repay or, judging from the xenophobia now raging there, no longer cares to admit.

Belfort feels no such reluctance. It honored its debt to Morocco at its 70th anniversary victory celebration on November 23rd, to which it personally invited Monique as an honored guest. There locals dressed in the distinctive Djellaba of the Goumiers led the parade. To underscore its gratitude, the town invited the sole surviving Moroccan Goumier fighter, long resettled in his native country, to the ceremonies. Too ill to travel, he sent his grandson in his place. The stand-in wore his grandfather’s immaculate, fresh-pressed uniform and carried a large board with his medals and a picture of him taken at the time of the battle pinned to it. The proxy looked like a clone of the man in the photograph. Monique introduced herself and told him her father, too, was a Goumier. The young man’s face brightened like a meadow when the sun breaks through clouds. There was an affectionate hand shake.

If there is any future anniversary celebration of the liberation of Belfort, it is likely that there will only be descendants of the fighters sent by families. As of 2015, only four men who served in the French army at the battle were alive. Two were present at the 70th anniversary; one was absent, and the other sent a representative. So this is probably Monique’s last chance to find and talk to someone who might have known her father or, at least, knows about the circumstances of his death.

As chance, luck, karma or grace — take your pick — would have it, one of the two was assigned the same table as Monique at a large luncheon held at the Novohotel, Belfort’s conference center. When the deputy mayor, also seated at the table, explained that Monique was there to honor her father’s death at Belfort, the soldier asked with whom he served. As soon as he heard the word “Goumier,” his face lit up and he exclaimed, “Madame, so was I!” Although he served in a separate unit, Monique asked him if he remembered or heard of the Caburet Farm where her father died. The brightness in his face hardened. You could almost hear a click of recognition at the name. Seated across from Monique, he leaned forward to make sure he would be heard. “Oh, there was some trouble there,” he says. “People were shooting at one another.” He paused, as if troubled by his own candor and its impact on Monique, and retreated within himself. “Mind you,” he cautioned, “this is only what I heard. I wasn’t there.”

“Trouble” is not a word normally used to describe combat. The word connotes confusion, error and mayhem. If any of these mushroom into conflict, it is generally smaller and shorter outbursts of violence such as barroom brawls, family feuds, gangland slayings and, in the case of Camille Frugier, friendly fire. He was the victim of a blunder not a battle. The “trouble” that cost Frugier his life at Belfort reinforces the tragedy that cost the townspeople at his birthplace of Oradour their lives. Frugier shares their status as an innocent.

BELFORT AND THE DIVIDED SOUL OF FRANCE: The Battle for Belfort wasn’t a fight for a city. It was a fight for a critical area that provided an entrance into Germany for the French and American armies in February 1945. This city of just over 50,000 people in the Alsace region is situated on a natural gap between the Vosges and Jura Mountains that stretch across eastern France and then along the Swiss border. It also serves as a geographical link between the Rhone and Rhine rivers — the former which runs through southeastern France from the Mediterranean to Switzerland’s Lake Geneva and the latter which runs along France’s northeastern border with Germany.

Given its strategic importance as the main access to France or Germany (depending on which side of the border you lived), Belfort has always been a target and trophy of war. First chartered as a French fortress rather than a city in 1226, Belfort became an Austrian territory in 1360 and was returned to France, via formal treaty, after the Thirty Years War in 1648. Although a time-line from this point forward until 1870 suggests stability, the many fortifications surrounding the city built by the French from the reign of King Louis XIV until well after the French Revolution make it clear Belfort’s impressive battlements were meant to deter future annexation by former captors. Such architecture proved a deterrence until 1870, when the Prussians besieged the city and won it after 73 days of constant bombardment. Nevertheless, they spared Belfort annexation, settling for the surrounding German-speaking areas of the Alsace region. During WWI, the Germans resumed severe bombardment.

Centuries of nationalist rivalry left the Alsace region with a large, stubborn residue of identity problems. These, in turn, contributed to — perhaps culminated in — profound loyalty conflicts during the German Occupation of WWII. At its very informative Web Site, the city of Belfort seeks to distance itself from the Vichy past by poo-pooing the notion its citizens feel any sense of Alsatian affiliation (a euphemism for pro-German identity) other than that of geography. Doth the Belfort chamber of commerce protest too much? The mere need for ridicule suggests national identity remains a sensitive issue.

To be fair, Belfort is not plagued by provincialism. Au contraire, it seems very much at home with, and a home for, present-day French multiculturalism. A plaque honoring its Goumier (Moroccan) liberators of 1944 sits in the center of the busy downtown area.

But the inclusiveness is incomplete. Others need to be admitted to the diversity of diasporas in 21st century France.

After the victory parade was over and we sat listening to semi-distant band music, a very dark African approached us. He wore filthy fatigues that have long served as his pyjamas. We assumed he was homeless, or one small degree of destitution away from it. “Hello, I’m from Senegal,” he said in very practiced English, by way of introduction. “We fought for France, too.” Monique and I smiled appreciatively at him. “Do you understand English?” he asked when we did not immediately engage him in conversation. We both nodded yes. Then he repeated with a kind of mechanical, long-benumbed pride: “I’m from Senegal. Have you heard of my country? It’s in Africa.” “Yes,” Monique reassured him. “We fought for France, too,” he continued. “Yes, we know,” Monique told him very kindly. “All the French colonies sent men to free Vichy France.” The African stared, slightly aslant, at Monique as if she didn’t quite get the point he was making. “I’m from Senegal. We fought for France, too,” he muttered, first to us and then to himself, as he walked away.

Maybe there needed to be a roll call of all the Muslim nations which contributed men to the Battle of Belfort. Of the 2,179 soldiers who died in the Battle of Belfort buried at the nearby necropolis, more than half are Muslims, all presumably from French colonies. World War II was the first, and probably last, Crusade in which Christian and Muslim fought side by side against bona fide ‘heathens.’ Yet that veteran from Senegal was excluded from the celebration in honor of the city he helped liberate. I felt pity for all those like him lost in a fog of war so permanent and thick that no sun, even one shining as brightly as the sun of this unseasonably warm November afternoon, can ever penetrate.

— David Federman, 12/04/20

484–412–8530 (office/home)